“It’s invisible, eh… this sickness in our hearts. It’s just a thought, really, a thought that makes us sick. It was someone else’s thought that was taught to us. It’s like they were so afraid of us that they had to teach us to be smaller than them…. And we learned it real good. Our kids are sick with it too. They got it from us. The drinking, the drugs, the violence, they learned it from us. When you look at it, when you really look at it, that’s where it comes from; it comes from us and we came from that school.”

Excerpt from Where the Blood Mixes by Kevin Loring

These words spoken by June, a residential school survivor in Kevin Loring’s Governor General’s Literary Award-winning play, Where the Blood Mixes, provide a stark reminder of the ongoing impact of residential schools.

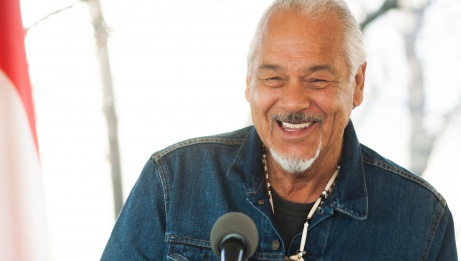

Where the Blood Mixes is also an example of how art can not only educate, but how it can heal. Kevin Loring, who is also Artistic Director of NAC Indigenous Theatre, has often said that stories – specifically Indigenous stories as told by Indigenous artists – are medicine.

“The truth exists in these stories,” says Lori Marchand, Managing Director of Indigenous Theatre. “Reconciliation is what we choose to do with the truth.”

A time to learn and reflect

September 30 is Orange Shirt Day and National Day of Truth and Reconciliation, a time when we wear orange to remember the Indigenous children who were sent to residential schools and never returned, and to honour the survivors, their families, and their communities. It is also a day for Canadians from coast to coast to coast to reflect on what Reconciliation means to them, or more precisely: “What will be my contribution to truth and reconciliation?”

From September 25 to 30, NAC Indigenous Theatre is proud to offer a series of activities under the theme Gnoondoon, Gwaabmin – an Anishinaabemowin expression meaning “I hear you, I see you.” – to educate and share the truths of Indigenous peoples with the rest of the country. Offerings includes reading lists, panel discussions, workshops, videos and colouring pages. It will also be an opportunity to share Indigenous experiences, culture and languages. National Day of Truth and Reconciliation activities were curated by Mairi Brascoupé and Kerry Corbière, members of the NAC Indigenous Theatre.

“These activities proudly proclaim: ‘We are still here’ and help us reclaim the things that residential schools tried to erase,” said Lori Marchand.

A story of allyship: P.H. Bryce

One of the week’s highlights is the Reconciling History Walking Tour led by Assembly of Seven Generations (A7G), an Indigenous youth-led non-profit in Unceded Algonquin Territory, and the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society. The tour is an opportunity to learn about the impact of residential schools on Indigenous children, as well as the legacy of Peter Henderson (P.H.) Bryce, whose 1922 report, detailing how colonial policies were killing children at alarming rates, was ignored.

Cindy Blackstock, Executive Director of the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society, has spearheaded an effort to shine a light on Bryce’s story of allyship, and to educate the public about the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s 94 Calls to Action.

“Faced with the truth of the children in unmarked graves, we often tell ourselves that ‘people back then did not know any better.’ Well Dr. Bryce knew better and did everything he could to save their lives and he is not alone,” says Blackstock. “Bryce knew that public pressure was the antidote to the government’s conscious choice to let the children die from preventable disease and so he published this report calling on the people to act. Some did, but when the headlines died so did the children.”

Leading the way to reconciliation: Indigenous artists

Cindy Blackstock believes the arts play a crucial role in Reconciliation and to shine the Truth on what happened to the children in residential schools.

“The potency of the arts in social justice cannot be overstated,” says Blackstock. “The contributions by iconic First Nations, Metis and Inuit artists such as Alanis Obomsawin and Buffy Sainte-Marie have inspired generations of Indigenous artists to give generously of their skills, talents, and time in making the world a more just, respectful, and loving place for all.”

These same artists, she adds, are having a tremendous impact on today’s Indigenous children, who are the key to true Reconciliation.

“I believe that children are the keepers of the possible,” she says. “By raising a generation of First Nations, Metis and Inuit children who never have to recover from their childhoods and a generation of other children who never have to say they are sorry we create a society where justice can take root and true reconciliation can prosper. I know we can get there because I have seen children of all diversities standing up for justice for First Nations children in the classrooms, courtrooms and on the steps of Parliament. When we trust children with the truth and give them a chance to stand up for the right thing, they show us loving justice.”