≈ 2 hours · With intermission

Last updated: January 29, 2019

It is with particular pleasure that I am introducing this strong, distinctive music to the fantastic NAC Orchestra and the lovely Ottawa audience this week, music by the grand Estonian master Arvo Pärt – whom I have the honour to know very well personally – and by Ralph Vaughan Williams. The challenge found in performing both Pärt’s and Vaughan Williams’ work is the need to take extra special care with the many details that might look simple and ordinary on paper, but which turn out to be essential for the understanding and intent of the music. Much of this detail is about atmosphere and sound.

I'm equally delighted to have the honour to work with Mr. Bronfman again, in one of the most extraordinary piano concertos ever written.

ARVO PÄRT, Trisagion

This is the first time the NAC Orchestra has performed Arvo Pärt’s Trisagion.

BEETHOVEN, Piano Concerto No. 4

Mario Bernardi led the NAC Orchestra in their first performance of Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 4 in 1970 with Claude Frank as soloist, and the Orchestra’s most recent interpretation of this work took place in 2016, with Rudolf Buchbinder at the piano and Alexander Shelley at the podium. Soloists who have performed this work with the Orchestra over the years include Radu Lupu, André Watts, Anton Kuerti, Garrick Ohlsson and Angela Hewitt.

VAUGHAN WILLIAMS, Symphony No. 5

This is the second time the NAC Orchestra has interpreted Vaughan Williams’ Symphony No. 5. The ensemble’s first performance took place in 1972 under the direction of Victor Feldbrill.

Repertoire

Trisagion

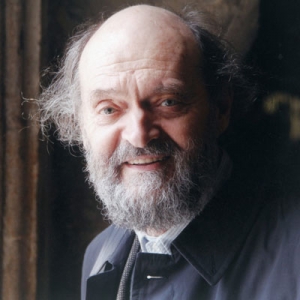

Born in Paide, Estonia, September 11, 1935

Now living in Berlin

Estonian-born Arvo Pärt is one of the most visible representatives of a new musical style that stresses simple materials, pure diatonic harmony, an austere mood, a sense of timelessness and haunting intensity. His musical training took place in Tallinn, where he remained until 1980. When he received permission to emigrate, his destination was initially Israel, but while en route there via Vienna, Pärt decided instead to settle in Berlin.

For a composer who not so long ago was all but unknown in the West, Pärt’s rise to fame has been astounding. His music has been performed by many of the world’s most prestigious artists and musical organizations, more than three dozen of his compositions are available on recordings, and his name is now mentioned in the same breath with those of John Adams, Henryk Górecki and John Tavener, among the modern composers whose names are synonymous with original and innovative work. Conductor Paul Hillier, an avid champion of Pärt’s music, summarizes his impact as follows: “Arvo Pärt’s music accepts silence and death, and thus reaffirms the basic truth of life, its frailty compassionately realized, its sacred beauty observed and celebrated. He… creates an intense, vibrant music that stands apart from the world and beckons us to an inner quietness and an inner exaltation.”

Trisagion was composed in 1994 and first performed that year on July 18 in Ilomantsi, Finland (about 300 miles northeast of Helsinki, on the Russian border) by Ensemble 21 conducted by Lygia O’Riordan. The fifteen-minute work is dedicated to the parish of Prophet Elias in Ilomantsi on the occasion of its 500th anniversary. Trisagion, meaning “thrice holy,” is the call or invocation to certain prayers in the Eastern Orthodox and Eastern Catholic Church. (Its counterpart in the Western Church is the Sanctus.) Sparsely-populated Ilomantsi (5,500 in 2014), incidentally, has the largest Orthodox minority (17.4%) among Finnish municipalities, and the largest wooden Orthodox church in all of Finland.

Trisagion is deeply meditative, spiritual, and rooted in tranquility, as is much of Pärt’s music. Rarely rising above piano, the music is constructed from simple chordal material that moves in short spurts punctuated by frequent silences. Kimmo Korhonen compares Pärt’s music to “a monastery of sound in the midst of a restless and conflicting world of music.”

Program notes by Robert Markow

Piano Concerto No. 4

Born in Bonn, December 16, 1770

Died in Vienna, March 26, 1827

It is the nature of many concertgoers today to test the waters of new music hesitantly and carefully. Imagine, then, the circumstances under which Beethoven’s Fourth Piano Concerto was given its first public performance – as one of seven(!) works all heard by the Viennese for the first time, all by the same composer, and four of them of major dimensions. This four-hour marathon concert took place on December 22, 1808 in Vienna’s Theater an der Wien. It was a freezing cold evening, which meant conditions inside the unheated hall were uncomfortable, to say the least. In addition, Beethoven’s music was generally considered to be advanced and difficult both to play and to understand. It was truly a daunting prospect for most concertgoers that night.

There are many bold, innovative and radical touches to this concerto. The most famous and most obvious of these is the unprecedented solo introduction. The orchestra responds in a harmonically remote key (another surprise), and goes on to present and develop other themes. The soloist reenters in a quasi-cadenza passage, and then joins the orchestra in a closely-woven tapestry of themes, motifs and rhythmic patterns.

The slow movement is, if anything, even more compelling and innovative than the first. In just a little over five minutes (one of the shortest slow movements of any well-known concerto) there unfolds one of the most striking musical dialogues ever written. Initially we hear two totally different musical expressions: the orchestra (strings only) in unison octaves – imperious, assertive, angry, loud, angular; and the solo piano fully harmonized – meek, quiet, legato. Over the span of the movement the orchestra by stages relents and assumes more and more the character of the soloist. Tamed, seduced, won over, taught, assuaged and conquered are some of the terms used to give dramatic or literary interpretation to this remarkable musical phenomenon.

The rondo finale steals in quietly, without pause, bringing much-needed wit, charm and lightness after the tense, dark drama of the slow movement. Trumpets and timpani are heard for the first time in the work. Like the first movement, it is full of interesting touches, including a rhythmic motto and a sonorous solo passage for the divided viola section. A brilliantly spirited coda brings the concerto to its conclusion.

Program notes by Robert Markow

Symphony No. 5 in D major

Born in Down Ampney, Gloucestershire, October 12, 1872

Died in London, August 26, 1958

“It is music imbued with what one can only call greatness of soul… the consummation of the lifetime’s work of a great and good man.” These words, by the English writer Wilfrid Mellers, sum up what many listeners must have felt about Vaughan Williams’ Fifth Symphony when it was still new in the early 1940s. The composer was well past 70, he had long been one of England’s most esteemed composers, and the music of this Fifth Symphony did indeed exude a valedictory aura. But Vaughan Williams lived on for many more years, dying shortly before his 86th birthday and having produced another four symphonies, thus joining such distinguished colleagues as Beethoven, Schubert, Spohr, Bruckner and Dvořák in the seemingly magical number of nine symphonies.

When Vaughan Williams’ Fourth Symphony appeared in 1935, its harshness and violence were interpreted as prophetic of the coming war. So too, the tranquil beauty and gentle radiance of the Fifth, which was first performed during the darkest days of World War II (June 24, 1943), were again seen as prophetic of a new age, when peace and joy would again reign in the world. But the facts confound the theory. Vaughan Williams began working on his Fifth Symphony in 1938, well before the war even began, and he even incorporated ideas from music written as far back as 1906 (The Pilgrim’s Progress).

The first performance was conducted by the composer at a Promenade Concert in London. Response from both critics and audience was highly favourable. Orchestras all over England quickly took it up, and the first American performance was given the following year by Artur Rodziński and the New York Philharmonic. The critic for the Christian Science Monitor warned his readers that this music would “shock young ears attuned to harsh discords.” It has been called the “Symphony of the Celestial City” (Michael Kennedy) and a “message of heavenly consolation” (Simona Parkenham).

The Fifth Symphony opens in a mood of utmost serenity, yet it is propelled by a subtle sense of motion generated by the gentle oscillation between C major and D major. Cellos and basses sound a deep pedal point on C, over which horns call faintly in D major, followed by a short motif in the violins in C major. From these mere scraps of musical mortar, Vaughan Williams builds an entire movement, a very Sibelian attribute justifying his dedication “with the sincerest flattery to Jean Sibelius, whose great example is worthy of imitation.”

The gentle horn call and the yearning violin motif continuously grow, expand and develop, often simultaneously, as happens within a few moments of their initial appearances. There are enough features of sonata-allegro form to justify the description, but this movement is really less concerned with the aspects of opposing and resolving tonalities as it is with the expansion and contraction of a single mood.

The Scherzo is all quicksilver, poured out in music of dark mystery bespeckled with strange glints of light. “It is like music for a ballet of hobgoblins, gargoyles and other fantastic creations,” writes Michael Kennedy. The Scherzo is the shortest of the symphony’s four movements, yet it is forged from no fewer than six themes or motifs that fly by with astonishing speed (“Arielesque,” Kennedy calls it).

The slow movement is called a “Romanza,” but romance, either in its amorous or literary implications, seems far removed from the spirit of this music, so heavily weighted with resignation, contemplation, and religious devotion. The solemn and ravishingly beautiful theme first played by the English horn recurs periodically throughout the movement (strings, horn, trumpet, and again at the end, horn, now muted), worked into a rich tapestry of additional themes. The movement’s central episode becomes restless as an anguished cry is raised in the woodwinds. After calm is restored, the various thematic ideas reappear in reverse order, and the movement ends in quiet meditation.

The finale is a passacaglia – a steadily recurring melodic pattern in the bass line over which other voices embellish it, develop variations on it or add new themes. Although Vaughan Williams does not adhere strictly to the form (as did Brahms in the finale of his Fourth Symphony), the movement, in Scott Goddard’s words, “is planned according to a vast design that comprehends large expanses in breadth, depth and height.” Many listeners find the experience akin to a long journey. The sense of arriving home again is unmistakable in the return of the symphony’s opening horn call, now proclaimed fortissimo by the full orchestra. From this climactic moment the tension subsides, and the symphony slowly fades into the furthermost reaches of audibility, taking us with it into a realm of serene radiance and peaceful meditation.

Critic Frank Howes captured the essence of this music when he wrote: “The Fifth Symphony written amid the noise of wars describes the nature of peace. Its peace is that which no pen can describe but which in default of better definition is called the peace that passeth understanding. It is the most successful attempt since Beethoven to use music as a direct penetration of the mystery of life.”

Program notes by Robert Markow

Artists

Principal Guest Conductor of the National Arts Centre Orchestra in Ottawa and Chief Conductor of the BBC Philharmonic Orchestra, John Storgårds has a dual career as a conductor and violin virtuoso and is widely recognized for his creative flair for programming as well as his rousing yet refined performances. As Artistic Director of the Lapland Chamber Orchestra, a title he has held for over 25 years, Storgårds earned global critical acclaim for the ensemble’s adventurous performances and award-winning recordings.

Internationally, Storgårds appears with such orchestras as the Berliner Philharmoniker, Munich Philharmonic, Orchestre National de France, Vienna Radio Symphony, and the London Philharmonic, as well as all of the major Nordic orchestras, including the Helsinki Philharmonic where he was Chief Conductor from 2008 to 2015. He also regularly returns to the Münchener Kammerorchester, where he was Artistic Partner from 2016 to 2019. Further afield, he appears with the Sydney, Melbourne, Yomiuri Nippon and NHK Symphony Orchestras as well as the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Chicago Symphony Orchestra, and New York Philharmonic.

Storgårds’s award-winning discography includes not only recordings of works by Schumann, Mozart, Beethoven, and Haydn, but also rarities by Holmboe and Vask, which feature him as violin soloist. Cycles of the complete symphonies of Sibelius (2014) and Nielsen (2015) with the BBC Philharmonic were released to critical acclaim by Chandos. November 2019 saw the release of the third and final volume of works by American avant-garde composer George Antheil. Their latest project, recording the late symphonies of Shostakovich, commenced in April 2020 with the release of Symphony No. 11. In 2023, Storgårds and the BBC Philharmonic were nominated for Gramophone magazine’s Orchestra of the Year Award.

Storgårds studied violin with Chaim Taub and conducting with Jorma Panula and Eri Klas. He received the Finnish State Prize for Music in 2002 and the Pro Finlandia Prize 2012.